In the realm of ecology, the term “pioneer” takes on a fascinating meaning, far removed from human exploration. When we talk about a Definition For Pioneer in an ecological context, we are referring to the hardy species that are the first to colonize barren or disturbed environments. These organisms, known as pioneer species, are the initial architects of new ecosystems, paving the way for more complex communities to follow.

Environments devoid of life, such as newly formed volcanic islands or land exposed by retreating glaciers, seem inhospitable. Yet, pioneer species are uniquely adapted to thrive in these challenging conditions. They are the vanguard of ecological succession, a process where ecosystems gradually evolve over time.

Surtsey, Iceland, provides a compelling example of pioneer species in action. Born from a volcanic eruption in the Atlantic Ocean in 1963, this island was initially a blank slate. However, it wasn’t long before life began to take hold. Sea rocket, sand ryegrass, and other resilient plants were among the first to establish themselves, demonstrating the tenacity of pioneer flora. Lichens and mosses soon followed, further enriching the nascent ecosystem.

Microorganisms are often the unsung heroes in this initial colonization phase. Bacteria, for instance, are frequently present even before visible plant life. They colonize bare rock surfaces and glacial expanses, initiating the biological processes crucial for soil development. Lichens, symbiotic partnerships between fungi and algae, are also key early colonizers. They extract essential water and minerals from the atmosphere, even secreting acids that slowly break down the rock itself. This breakdown, combined with the decomposition of lichens, starts the long process of soil formation. Moreover, these pioneers contribute to soil fertility by fixing nitrogen and adding carbon, crucial elements for plant growth. Mosses, with their rock-weathering acids, further accelerate this soil development.

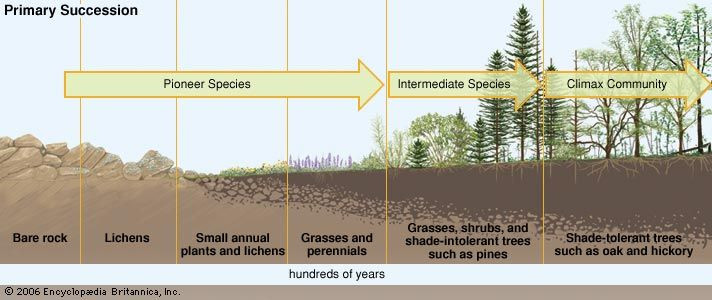

Primary ecological succession, the process initiated by pioneer species, unfolds over extended periods. Starting in barren zones, such as rock exposed by retreating glaciers, pioneer species like lichens, mosses, fungi, and certain microorganisms are the first inhabitants. These hardy organisms, adapted to harsh conditions, gradually transform the rock into soil capable of supporting more complex plant life, such as grasses. As grasses take root, they further modify the soil composition, making it hospitable for subsequent plant species.

The arrival of wind and water-borne seeds and spores introduces new fungal and plant species, including grasses and ferns, to the developing environment. As vegetation establishes itself, animal pioneers, often invertebrates like ants, worms, and snails, join the community. These creatures play a vital role by processing plant litter and aerating the developing soil, further enhancing its quality.

Eventually, seeds of larger plants, carried by wind, water, or birds, arrive. These intermediate species, such as shrubs and small trees, grow taller and begin to shade out the pioneer species that require direct sunlight. Over time, the environment shifts, becoming less favorable for the original pioneers. They are gradually replaced by these intermediate species, marking a further stage in ecological succession. This process culminates in a climax community, a stable and mature ecosystem that can persist for centuries, a testament to the foundational work of the initial pioneer species. Thus, the definition for pioneer species extends beyond just being the first; they are essential catalysts in the creation and evolution of ecosystems.

primary ecological succession

primary ecological succession