In the annals of technology and chess history, the narrative of computer chess is punctuated by visionary figures who dared to dream of machines capable of strategic thought. Long before supercomputers like Deep Blue and Stockfish dominated chess engines, there were pioneers who laid the groundwork for artificial intelligence in chess. Stepping away from the automata of the Enlightenment, the early 20th century saw the emergence of real attempts to create chess computers, spearheaded by inventive minds who could be considered the true ‘Mechanical Turks’ of their time in the realm of computation.

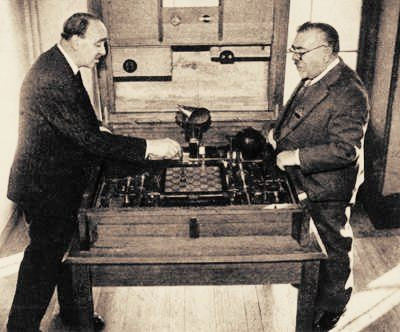

One such luminary was Leonardo Torres y Quevado, a Spanish civil engineer and mathematician. As early as 1912, Torres y Quevado embarked on constructing ‘El Ajedrecista’ (The Chessplayer), a groundbreaking mechanical automaton. This prototype was meticulously programmed to play a King and Rook versus King endgame automatically from any given position. The public unveiling of El Ajedrecista at the University of Paris in 1914 was met with considerable excitement. Initially, mechanical arms physically moved the chess pieces, but by 1920, Torres y Quevado refined his creation, incorporating electromagnets beneath the board. This ingenious upgrade gave spectators the eerie impression of a chess game being played by unseen forces.

‘El Ajedrecista’ stands as one of the earliest autonomous machines capable of engaging in chess. It was designed to consistently achieve checkmate using a straightforward algorithm. While it might not always find the most efficient checkmate or adhere to the 50-move rule, it was remarkably reliable within its defined parameters. As long as the configuration involved White’s King and Rook against Black’s King, the machine could invariably deliver checkmate from any starting position. The device was also equipped to detect and signal illegal moves and positions with a light bulb, preventing any attempts to manipulate it with invalid plays. The declaration of checkmate was quite theatrical, announced by a sound effect, a recorded voice, and a speaker proclaiming “jaque mate!”.

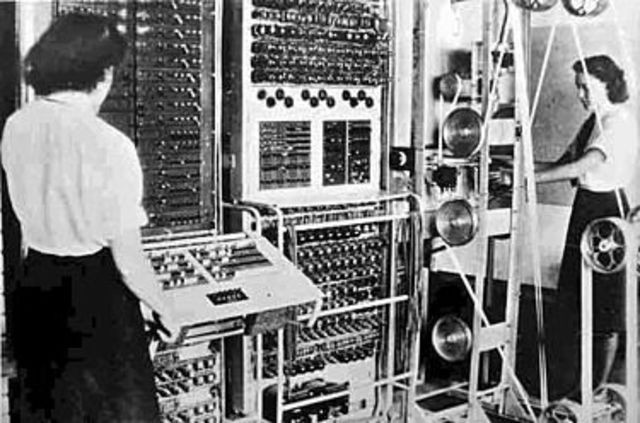

Transitioning from mechanical ingenuity to computational theory, the story of Computer Chess Pioneers takes us to Alan Turing, a British mathematician and computer scientist of immense stature. Turing, born in 1912, is celebrated for his foundational contributions to theoretical computer science, which were instrumental in shaping the development of modern computers. In 1948, Turing, in collaboration with his colleague Prof. David Gawen Champernowne at King’s College, Cambridge, conceived ‘Turochamp’. The name itself was a portmanteau of their surnames, Turing and Champernowne. Despite lacking a physical computer to run it, Turochamp became arguably the first historical computer chess program, existing as a set of rules and calculations.

Alan Turing, a pivotal computer chess pioneer, alongside a representation of the Turochamp program he co-developed.

Alan Turing, a pivotal computer chess pioneer, alongside a representation of the Turochamp program he co-developed.

In the summer of 1952, a landmark event occurred when Turing manually played a game against his colleague Alick Glennie, a computer specialist, using the Turochamp program. This match, meticulously recorded, saw the Turochamp program, operated by Turing himself with pencil and paper, lose to Glennie in 29 moves. Each move in this paper-based computation took around half an hour. Turing’s method involved calculating all potential moves, anticipating opponent responses, assigning point values to game states, and selecting the move that promised the highest average point value. This painstaking process allowed Turochamp to play a complete chess game against a human opponent, albeit at a beginner level, entirely through manual calculation.

A visual representation of the manual computation process for Turochamp, highlighting the paper-based approach of this computer chess pioneer's program.

A visual representation of the manual computation process for Turochamp, highlighting the paper-based approach of this computer chess pioneer's program.

Champernowne recounted the strategic approach behind Turochamp: “Most of our attention went to deciding which moves were to be followed up… Captures had to be followed up at least to the point where no further captures was immediately possible. Check and forcing moves had to be followed further. We were particularly keen on the idea that whereas certain moves would be scorned as pointless and pursued no further others would be followed quite a long way down certain paths. In the actual experiment I suspect we were a bit slapdash about all this and must have made a number of slips since the arithmetic was extremely tedious with pencil and paper. Our general conclusion was that a computer should be fairly easy to program to play a game of chess against a beginner and stand a fair chance of winning or least reaching a winning position.” (Copeland, 2004). Wilhelmina, Champernowne’s wife, holds the distinction of being the first opponent to play a test game against Turochamp, marking another unique moment in computer chess history.

Wilhelmina Champernowne, the first person to play against Turochamp, a key moment in the experience of early computer chess pioneers.

Wilhelmina Champernowne, the first person to play against Turochamp, a key moment in the experience of early computer chess pioneers.

Though the original Turochamp algorithm was lost, it was reconstructed in 2000 by Ken Thompson and Mathias Feist. Turing had begun efforts to implement Turochamp on the Ferranti Mark 1 computer in 1950, but his untimely death in 1954 left this work unfinished. The 2000 reconstruction and digitization preserved the essence of Turochamp, with the program still operating on a two-move lookahead, a stark contrast to the advanced chess engines of that era like IBM’s Deep Blue. This reconstructed engine was made publicly available via ChessBase, allowing enthusiasts to use it as a sparring partner in chess engine programs like Fritz or Rykba, offering a glimpse into the rudimentary yet historically significant past of computer chess.

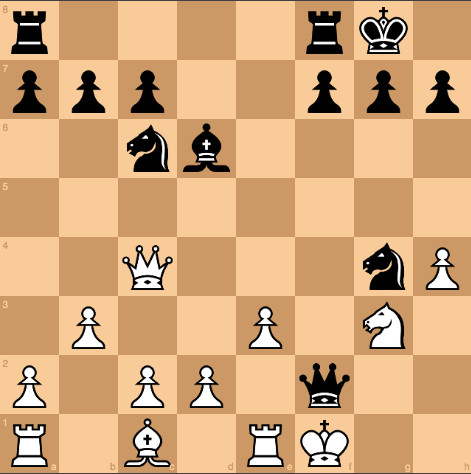

The reconstructed Turochamp algorithm, a digital revival of the computer chess pioneer's lost program.

The reconstructed Turochamp algorithm, a digital revival of the computer chess pioneer's lost program.

In a remarkable encounter, Turochamp (Reconstructed) faced Garry Kasparov, one of chess’s all-time greats. At the 2012 Alan Turing Centenary Conference in Manchester, UK, Kasparov played a public match against this 60-year-old program, defeating the digital version in just 16 moves. Despite the swift victory, Kasparov expressed admiration for the machine and its creator, stating, “It was an outstanding accomplishment… Alan Turing is one of the very few people about who you could say that if he had lived longer the world would be a different place.”

Garry Kasparov playing against the reconstructed Turochamp in 2012, a symbolic match between a chess grandmaster and a computer chess pioneer's creation.

Garry Kasparov playing against the reconstructed Turochamp in 2012, a symbolic match between a chess grandmaster and a computer chess pioneer's creation.

Kasparov at the Alan Turing Centenary Conference, reflecting on the legacy of a computer chess pioneer.

Kasparov at the Alan Turing Centenary Conference, reflecting on the legacy of a computer chess pioneer.

The contributions of Leonardo Torres y Quevado and Alan Turing stand as monumental first steps in the journey of computer chess. They are true computer chess pioneers, whose ingenuity and foresight paved the way for the sophisticated AI-driven chess engines we see today. Their legacy reminds us that even the most complex technological achievements often begin with the visionary ideas of individuals who dare to explore the uncharted territories of computation and artificial intelligence.