The late afternoon in August 2020 cast a muted, gray light, the day fading into a cool sunset. Friends, island locals, invited me onto their thirty-foot wooden sportfishing boat, a sleek vessel they once used to take Andy Griffith out when he became too frail to navigate his own boat.

They knew Andy intimately. Sharing drinks, they recounted stories of times spent with him on Roanoke Sound. As my friend steered the boat from the Manteo dock in the downtown area, we moved out of Shallowbag Bay. We cruised slowly northward on the sound, gently rocking near a sandspit. This was a place where Andy would often anchor his pontoon boat, always filled with companions – he disliked being alone, they told me – and where he fiercely participated in volleyball games.

We passed by Andy’s last grand house, barely visible through the pine trees. It sits just south of the Waterside Theatre, the venue for The Lost Colony outdoor drama. This is where Andy’s journey began in the summer of 1947, marking a true pioneer portal into his celebrated career.

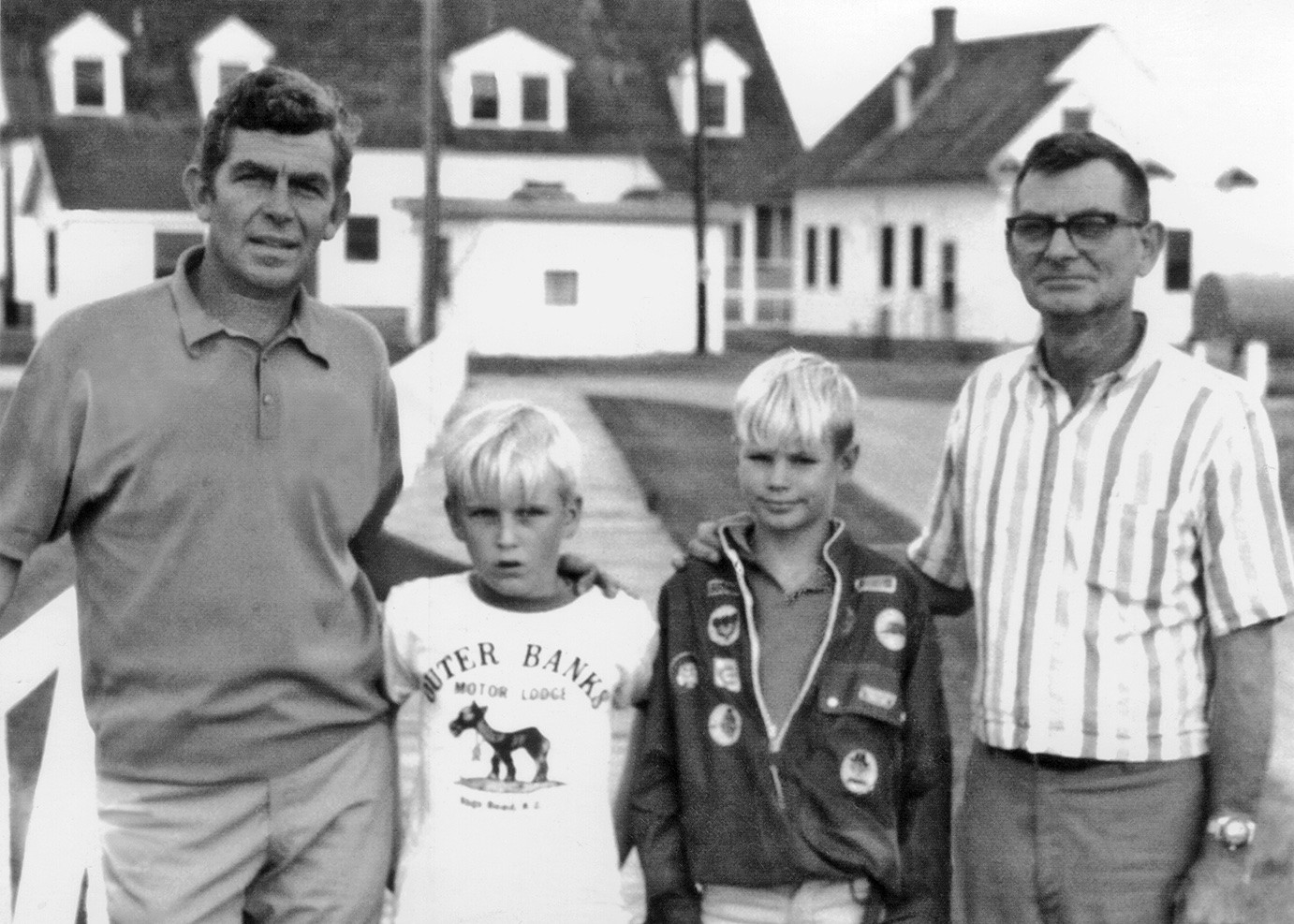

Andy Griffith, Doc Harvey, and their sons at the Oregon Inlet Coast Guard Station, October 1968

Andy Griffith, Doc Harvey, and their sons at the Oregon Inlet Coast Guard Station, October 1968

His experiences working in that play served as a lifelong anchor. Throughout his six-decade career, Andy regularly took red-eye flights eastward from Los Angeles. He was always returning home from the city that facilitated his success to the island that initially gave him that opportunity. He would enjoy evening drinks, high above the twinkling lights of countless homes across the nation, homes of his devoted fans. These fans initially watched his eponymous show on prime-time television, antennas reaching for signals, and later in daily reruns on flat screens.

For the final leg of his journey, once he achieved fame, he would board a small, puddle-jumper plane to his island. The sight of the shimmering water and sandy beaches lined with pines always filled him with joy. This place eventually became his permanent home.

As my friends shared their anecdotes and we glided across the serene sound where Andy spent many of his happiest moments, the legend of this island icon came to life.

What was the true essence of Andy Griffith? In 2022, the tenth anniversary of his passing, this question continues to resonate with fans across the country. We primarily know him as Sheriff Andy Taylor, the iconic character from The Andy Griffith Show.

Andy often remarked that he was unlike Taylor, not nearly as virtuous. However, he acknowledged that parts of himself were indeed reflected in the character, notably sharing his first name. In numerous interviews, he offered glimpses into his real self, occasionally speaking openly about his artistic struggles and self-doubt. Yet, he remained elusive about his complete identity, carefully maintaining a private persona.

His closest confidants on the island largely respected his privacy, remaining silent after his death on July 3, 2012. However, by the summer of 2018, while I was researching another book about his island, I sensed a shift. My sources began sharing personal scrapbooks and fascinating stories about Andy. I listened, captivated. Andy’s island friends were finally willing to speak.

Aerial view of Andy Griffith's original island house

Aerial view of Andy Griffith's original island house

Their aim was to clarify the true nature of this complex man, to separate the myth from the reality, however challenging that might be. He was a skilled skeet shooter and enjoyed drinking, yet he also possessed a personal form of religiousness. He cherished the tranquil, unhurried pace of island life, where he could casually visit a friend, and they would bring out guitars and Budweisers, spending hours strumming on the porch and conversing. He was alternately kind, generous, irritable, and frugal. He often quietly supported underdogs, mirroring his own early experiences. He valued loyalty yet was seldom cynical, often optimistic, maintaining a youthful curiosity and wonder about the world, sometimes even appearing naive in his later years. He could be humble at times but generally preferred to be the center of attention.

He was both gentle and unpredictable, comforting islanders in times of grief and offering wise counsel, yet also capable of accidentally discharging a shotgun in his house or forcefully punching a door in his California home, resulting in a broken hand that was written into The Andy Griffith Show as an injury Sheriff Taylor sustained in a prisoner scuffle.

Andy was a notorious practical joker, once attempting to trick a local friend into eating a horse-manure sandwich disguised as a hamburger. He had a passion for anything with an engine and wheels, a product of the Great Depression who collected vintage cars and enjoyed driving them around, though some friends noted he wasn’t a particularly attentive driver, often distracted by his surroundings. He jokingly used derogatory terms but quietly defended gay friends against religious leaders who preached against gay marriage, recognizing the hurt it caused.

He could party with the best of the Outer Bankers, reportedly consuming a fifth of liquor in a night in his younger days, and also study his Bible with the devoutness of the most sober islanders, sometimes within the same day, simply another soul navigating life’s path. He loved singing gospel songs and even served as the choir director at Mount Olivet United Methodist Church in Manteo for a year.

At other times, he would dock his pontoon boat at the popular soundside bar, the Drafty Tavern, to replenish supplies with friends – pizzas and cases of beer – singing loudly, “When the saints go marching out,” his playful adaptation of the gospel classic, as they carried their bounty back to his boat.

He made people laugh and charmed them with his country-boy persona, both on screen and on the island. Those close to him say the lines sometimes blurred, making it difficult even for them to distinguish the real Andy. But when he expressed his sincere “I ’preciate it” for acts of kindness, large or small, they knew they were seeing the genuine man.

He was a comedic genius, and at times, demonstrated dramatic brilliance, yet he left behind few personal writings. His driving force was storytelling. Early in his career, during his powerful dramatic performance as Lonesome Rhodes in the 1957 film A Face in the Crowd, director Elia Kazan pushed him to delve into the depths of that troubled character, exploring Andy’s own darker aspects. “It’s a tremendous performance,” Ron Howard told me, “but it took a toll on him.”

When Andy arrived on Roanoke Island in 1947 as a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to participate in The Lost Colony, he was still developing, hitchhiking around the island and relying on rides from friends as he didn’t own a car. He was restless and ambitious, open to all opportunities, having experienced his potential at the Carolina Playmakers. This group had, decades earlier, launched another North Carolina literary genius, novelist Thomas Wolfe. Chapel Hill broadened Andy’s perspective, but the island expanded his horizons immeasurably.

While his comedic breakthrough is often attributed to his monologue, “What It Was, Was Football,” his 1953 Raleigh debut actually followed his pivotal experience on the island the year before. And the Raleigh performance was arranged by a close friend from The Lost Colony.

Andy Griffith at the Pioneer Theater in Manteo in 1957 at the premiere of “A Face in the Crowd.”

Andy Griffith at the Pioneer Theater in Manteo in 1957 at the premiere of “A Face in the Crowd.”

The island, particularly as Andy encountered it in the late 1940s when downtown Manteo streets were paved with oyster shells, held an endless fascination. Ancient live oaks and yaupon trees, a grapevine with centuries of history, moody sound waters surrounding it, and a garden of stone on a quiet side street with unique gravestones each telling their own stories. But most importantly for Andy were the creative human energies, his fellow actors and the locals who shared their stories. It was, he would later describe, an “emotional draw.” Manteo became his personal pioneer portal to self-discovery.

He encountered a community of daring individuals and found a way to connect with their maritime culture and make it his own. He listened intently to islanders conversing and interacting, transforming these observations into comedic art, a style uniquely his. Like much great comedy, it was rooted in the comedian’s own insecurities.

Andy wasn’t particularly scholarly, but he possessed keen street smarts and immense ambition. He instinctively recognized three fellow actors who could alleviate his anxieties through their art and propel his career, and he consistently turned to them for support. He was energized by the competitive atmosphere among the cast and the romantic dynamics within the group and between them and the locals. He absorbed the islanders’ adventurous spirit, soon taking risks on Broadway and in Hollywood.

The islanders embraced him, providing the sense of belonging he had long craved, having been labeled “white trash” by a classmate in his hometown of Mount Airy, North Carolina. He was an only child with loving and supportive parents – a mother who instilled in him a love of music and a father whom Andy described as a natural comedian.

However, Andy hadn’t felt fully accepted in his hometown. “Once you have s—— on your shoes, you can’t shake it off,” he confided in a 1982 unpublished interview with Outer Banks author David Stick. “You cannot get it off. But when I came here [to the island], I was in the same boat everybody else was… Everybody started from scratch here.”

He never forgot this, the boy who had never seen the ocean before arriving on the island, eventually becoming one with the local community. He was there for them in times of need, from arranging a jet flight home from Texas for a friend battling cancer to visiting a sick companion in Chapel Hill and singing at a friend’s wedding. “He did a lot of things nobody ever saw,” said longtime island friend, Della Basnight.

Andy infused lessons learned on the island into his show. “If Mayberry is anywhere, it is Manteo,” he told Manteo author Angel Ellis Khoury for her 1999 book Manteo: A Roanoke Island Town. He also clarified, “Mayberry is not Mount Airy.”

Mount Airy annually attracts thousands of visitors to its September celebration of The Andy Griffith Show, Mayberry Days, claiming to be the inspiration for the fictional town. Geographically, the show, with its references to foothills and lakes, was loosely based in Andy’s hometown. However, Manteo, with its historic courthouse at the heart of downtown streets surrounded by modest businesses and welcoming homes, more closely resembled the town setting.

Crucially, the overarching theme of supporting flawed friends and even strangers, rarely judging them even when they strayed from strict rules, and using laughter as a healing force, came directly from Andy’s heart and his deep connection to his island. This was a feeling he never experienced in Mount Airy. In a 1960 episode of the show, “Stranger in Town,” Sheriff Taylor concludes with a powerful speech to Mayberry residents about welcoming a quirky newcomer without judgment.

As Andy’s star rose, he broke through his carefully maintained privacy to give back to Manteo in significant ways. He became a powerful advocate for the town’s revitalization and preservation, leveraging his friendships with governors and their access to resources. He helped establish the Outer Banks Community Foundation, assisting locals facing various hardships. When Andy made his comeback in the 1980s with Matlock, the flawed, funny, and successful lawyer, he filmed a segment on the island, injecting much-needed funds into the community, a triumphant homecoming.

Later, to support local grocery store owners against the encroachment of a chain store, Andy spoke out at meetings and filmed a commercial, pro bono, dedicating hours to retakes to perfect it, treating the production with the same seriousness as his television shows. He also championed initiatives to provide Manteo children with free internet access for their schoolwork.

While maintaining a California residence for much of his career, Andy remained deeply connected to his Roanoke Island home, its people, and The Lost Colony. He and his first wife formed a bond during their time in the play before marrying. Years later, he met his third wife through the colony as well, the woman who remained by his side until his passing.

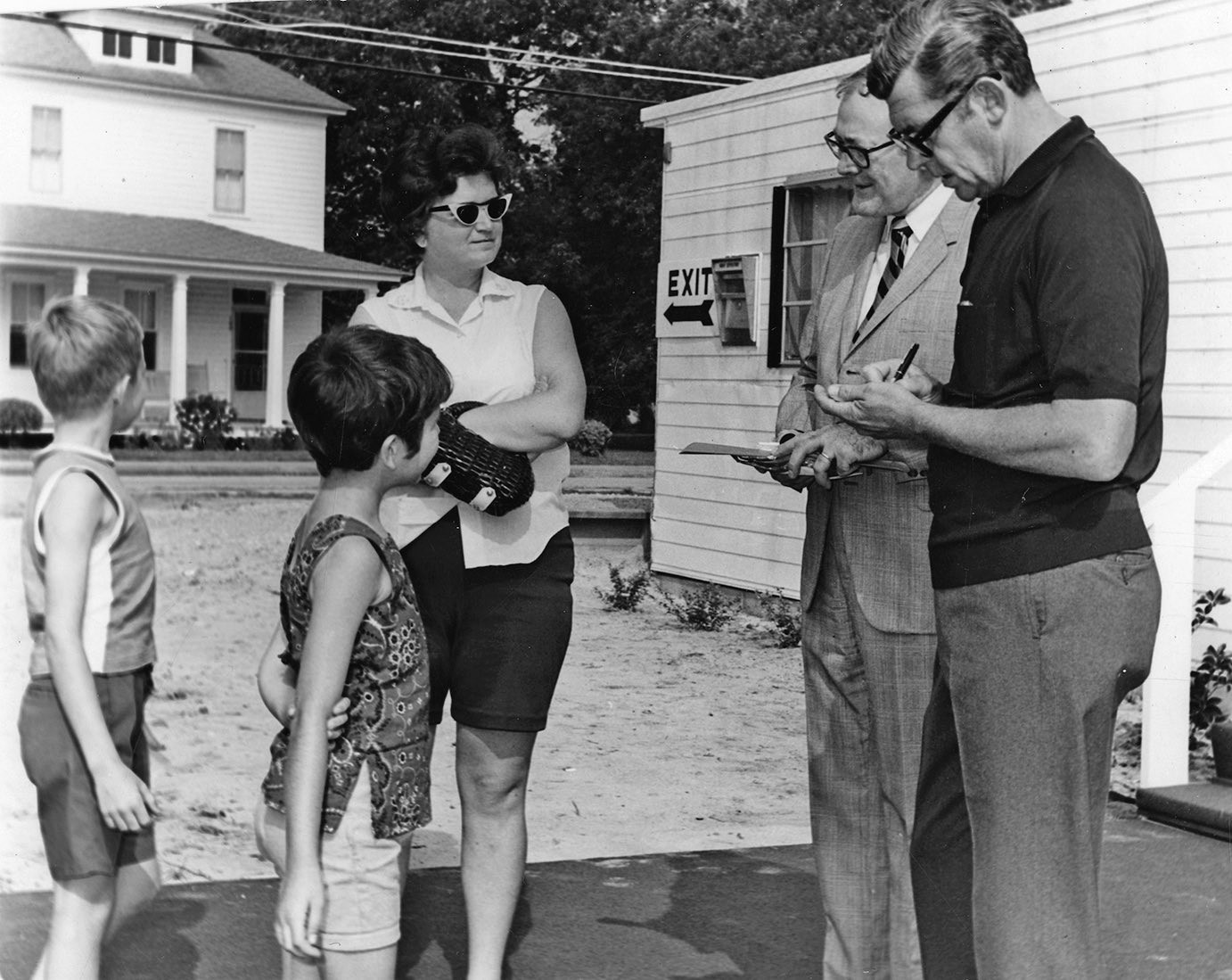

Andy Griffith signing autographs at the opening of an East Carolina Bank branch in Manteo in the summer of 1969.

Andy Griffith signing autographs at the opening of an East Carolina Bank branch in Manteo in the summer of 1969.

Summer after summer, night after night, Andy would dock his boat at the Waterside Theater and walk barefoot backstage, a tall, relaxed figure, often with a cigarette in hand, encouraging young actors and actresses, inspiring them to pursue their dreams as he had. He would then quietly slip away into the moonlit waters before the show began, not wanting to overshadow their moment.

He inspired many Lost Colony participants, including North Carolina native Leon Rippy, who went on to become a successful character actor, notably in films like The Patriot, Saving Grace, and Deadwood.

For the Lost Colony company and longtime Outer Bankers who frequently saw Andy walking barefoot around Manteo, he embodied coolness, the embodiment of hard work paying off, and the joy of unwinding with good times, Hollywood glamour returning home to connect with them. Long before Jimmy Buffett, Andy defined the fun-loving island lifestyle. When Buffett performed in Raleigh in 2014, two years after Andy’s death, he and his band played the theme song from The Andy Griffith Show, “The Fishin’ Hole.”

Andy, like many of his fellow islanders and Southern artists such as Hank Williams Sr., Jerry Lee Lewis, and Johnny Cash, with whom he co-starred in a TV movie, was shaped by the tension between spiritual aspirations and earthly struggles, a common theme in the Christ-centered South.

Andy initially aspired to be a Moravian minister, then spent much of his career balancing hard work and hard play before, in his later years, releasing gospel albums and taking on edgy film roles that recalled the powerful potential he displayed as Lonesome Rhodes, gaining a new generation of admirers.

He had long reduced his consumption of hard liquor but continued to enjoy white wine, albeit sparingly, until near the end of his life. Shortly before his death, he reaffirmed his faith in a small church near his beloved Roanoke Sound. He was mourned by North Carolina governors, the president, and The New York Times.

His remarkable journey from early childhood poverty often led to descriptions emphasizing “grit and determination,” and while those qualities were present, there was nothing ordinary about this American original. He was deeply committed to being uniquely funny, achieving significant financial success through it, and generously giving back to his island. This complex reality is the true and complete Andy, a pioneer spirit who found his portal to success and fulfillment in Manteo.

In his complexities, he was much like many of his fellow islanders: he ultimately wanted to be a good man.

John Railey, the former editorial page editor of the Winston-Salem Journal, can be reached at [email protected]. He is the author of The Lost Colony Murder on the Outer Banks: Seeking Justice for Brenda Joyce Holland and Andy Griffith’s Manteo: His Real Mayberry.

More by this author

Andy Griffith’s Manteo, copyright 2022, is reproduced with the permission of The History Press of Charleston, S.C.