In the vast and varied landscapes of our planet, life often emerges in the most unexpected and seemingly inhospitable places. This remarkable phenomenon is largely due to the action of Pioneer Organisms, the hardy species that are the first to colonize barren environments. From volcanic islands rising from the sea to rocky terrains left behind by retreating glaciers, these biological trailblazers pave the way for more complex ecosystems to develop. Understanding pioneer organisms is crucial to grasping the fundamental processes of ecological succession and ecosystem establishment.

Microorganisms are frequently the vanguard in newly formed habitats. Bacteria, for instance, are often among the first pioneer organisms to appear, colonizing surfaces like bare rock and even glacial ice. Their adaptability allows them to thrive where resources are scarce and conditions are extreme. Following closely behind, or sometimes concurrently, are lichens. These fascinating composite organisms, resulting from a symbiotic partnership between fungi and algae, are quintessential pioneer organisms. Lichens possess the unique ability to extract essential moisture and nutrients directly from the atmosphere – from raindrops, humidity, and airborne dust.

As lichens establish themselves, they initiate a crucial process: soil formation. They secrete acids that gradually break down the underlying rock. When these pioneer organisms die and decompose, their organic matter mixes with the fragmented rock particles, creating a rudimentary soil. Furthermore, both microorganisms and lichens enhance soil fertility by performing vital ecological functions such as nitrogen fixation and carbon enrichment. Mosses represent another significant group of early pioneer organisms. Similar to lichens, mosses contribute to the weathering of rocks through the release of acids, further aiding in soil development and preparing the ground for subsequent plant life.

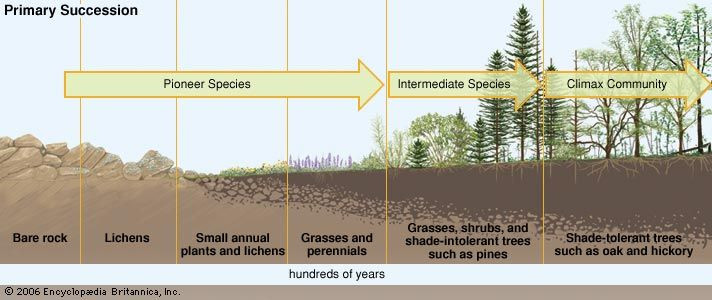

The ecological process initiated by pioneer organisms is known as primary succession. This process unfolds in areas devoid of pre-existing soil, such as newly exposed rock after glacial retreat or volcanic eruptions. The initial inhabitants, the pioneer organisms like lichens, mosses, fungi, and certain resilient microorganisms, are uniquely adapted to endure these harsh, resource-poor conditions. Over extended periods, often spanning centuries, these pioneer species fundamentally alter the environment, transforming bare rock into soil capable of supporting more complex plant communities, starting with simple plants like grasses.

The arrival of grasses marks a new phase in ecological succession. These plants further modify the developing soil structure and composition, making the habitat more hospitable. This improved environment then becomes suitable for colonization by other plant types. Each successive wave of species modifies the habitat, altering factors such as shade levels and soil nutrients, creating a dynamic progression. Ultimately, ecological succession culminates in a climax community, a stable and mature ecosystem that can persist for centuries.

Seeds and spores of various organisms are dispersed by wind and water, reaching these newly formed environments. They lodge in crevices and start to germinate in the soil created by the initial pioneer organisms. Among these newcomers are fungi, grasses, and ferns, expanding the biodiversity of the nascent ecosystem. As these plants and fungi grow and establish themselves, animal pioneer species begin to arrive. These are often invertebrates, such as ants, worms, and snails. These animal pioneer organisms play a crucial role in the developing biological community by processing leaf litter and other plant material, contributing to nutrient cycling and aerating the soil.

In later stages, seeds of taller plants, including shrubs and trees, are introduced, often carried by wind, water, or birds. These intermediate species grow taller, casting shade that gradually deprives the initial pioneer organisms of the sunlight they require. Consequently, the environment becomes progressively less favorable for the original pioneer plants and fungi. They eventually decline locally, being slowly replaced by these more competitive intermediate species. This ongoing process of colonization and species replacement is fundamental to the development of diverse and mature ecosystems, all starting with the indispensable role of pioneer organisms.

Primary ecological succession stages, illustrating pioneer species gradually transforming bare rock into a climax community over hundreds of years.

Primary ecological succession stages, illustrating pioneer species gradually transforming bare rock into a climax community over hundreds of years.