Each year on July 24th, Utah comes alive with vibrant celebrations for Mormon Pioneer Day. This unique state holiday mirrors the enthusiasm of Independence Day with parades, rodeos, fireworks, and even a marathon, all set against a backdrop of red, white, and blue. However, Mormon Pioneer Day holds a distinct significance, commemorating the arrival of Mormon pioneers in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847.

The term “Mormon” is historically linked to churches originating from the teachings of Joseph Smith. The largest denomination, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, while rooted in this heritage, has in recent times moved away from the “Mormon” label. Regardless of terminology, Pioneer Day marks a pivotal moment in the history of this faith and the state of Utah.

The journey to the Salt Lake Valley was arduous. These early Latter-day Saints were refugees, having traveled over a thousand miles from Illinois. On July 24, 1847, after months of relentless travel, Brigham Young, then the church president, first glimpsed the valley and declared, “This is the right place.” This declaration solidified the Salt Lake Valley as the new home for these pioneers.

For members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Pioneer Day is observed with church-centered activities. These can include special talks, dances, communal potluck meals, and even symbolic reenactments of the original pioneers’ trek along the Mormon Trail using handcarts. Salt Lake City hosts the grand “Days of ’47” parade, a spectacle of elaborate floats that interpret a different pioneer-related theme each year.

As a historian specializing in Mormon migration and immigration, I observe that the elaborate celebrations of Pioneer Day reflect the complex and evolving relationship between the church, notions of nationalism, racial identity, and historical narrative. While each commemoration highlights tales of pioneer hardship and heroism, it predominantly focuses on a single migration story within the broader, more diverse history of both the church and the region.

The Church in Motion: A History of Gathering

Joseph Smith established the LDS church in 1830 in upstate New York. From its inception, movement has been a defining characteristic of its history. Smith proclaimed revelations and visions that urged Latter-day Saints to gather and prepare for the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. The church doctrine emphasized the concept of Zion, a gathering place for God’s people before Jesus’ return, drawing from biblical references to Jerusalem and Israel. Nineteenth-century Latter-day Saints believed that by converting individuals to their faith and facilitating their collective migration, they were actively building Zion.

In its initial decades, the LDS church relocated its headquarters several times, establishing communities in New York, Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois. Each relocation was unfortunately accompanied by conflict with existing communities who viewed the burgeoning church with suspicion. This distrust frequently escalated into discrimination and, tragically, outright violence. Following the assassination of Joseph Smith by a mob in 1844, Brigham Young assumed leadership and led a significant portion of the Mormon population on a demanding exodus to the West, ultimately reaching Utah.

The Western Expansion and Establishing Autonomy

When the Latter-day Saints arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, the territory was under Mexican jurisdiction. However, this changed swiftly the following year when the United States acquired the land as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which concluded the Mexican-American War and transferred vast Western territories to U.S. control.

Despite being under U.S. sovereignty, Utah did not achieve statehood for another half-century. In the interim, the Latter-day Saints in Utah enjoyed a period of relative autonomy. To bolster their community through continued immigration, Brigham Young instituted a Perpetual Emigrating Fund. This innovative micro-loan system provided financial assistance to church converts, enabling them to migrate to Utah from both within the United States and internationally.

Deep-seated mistrust of the U.S. government, stemming from prior experiences of persecution, was prevalent among church members. Conversely, many Americans harbored suspicion towards the LDS church, exacerbated by the then-practiced doctrine of polygamy – a practice that church leaders officially discontinued around 1900.

Adding to the complexity, some 19th-century Americans categorized Mormon immigrants, predominantly from Europe, as racially “nonwhite.” This coincided with rising anti-immigrant sentiments, leading to instances where critics erroneously conflated Mormon immigrants with Chinese and Muslim immigrants, fueled by xenophobia and religious prejudice. The U.S. federal government actively attempted to curtail Mormon immigration through various measures, including the Immigration Act of 1891, which barred individuals who practiced or supported polygamy from entering the country. Despite these restrictions, hundreds of Latter-day Saints continued to immigrate to Utah annually, driven by faith and community ties.

Unveiling Overlooked Narratives

Migration narratives are central to the identity and pride of many Utah residents, and Pioneer Day celebrations boast a long and rich history. Just two years after the initial arrival in 1847, Latter-day Saints commenced commemorating the anniversary. Early celebrations featured cannon fire salutes, musical performances, bell ringing, and orations.

Later Pioneer Day observances incorporated reenactments. The 50th anniversary in 1897 saw participants reenacting segments of the arduous trek along the Mormon Trail. A procession of wagons and horse-drawn floats also took place, a spectacle that evolved into the formalized “Days of ’47” parade we see today.

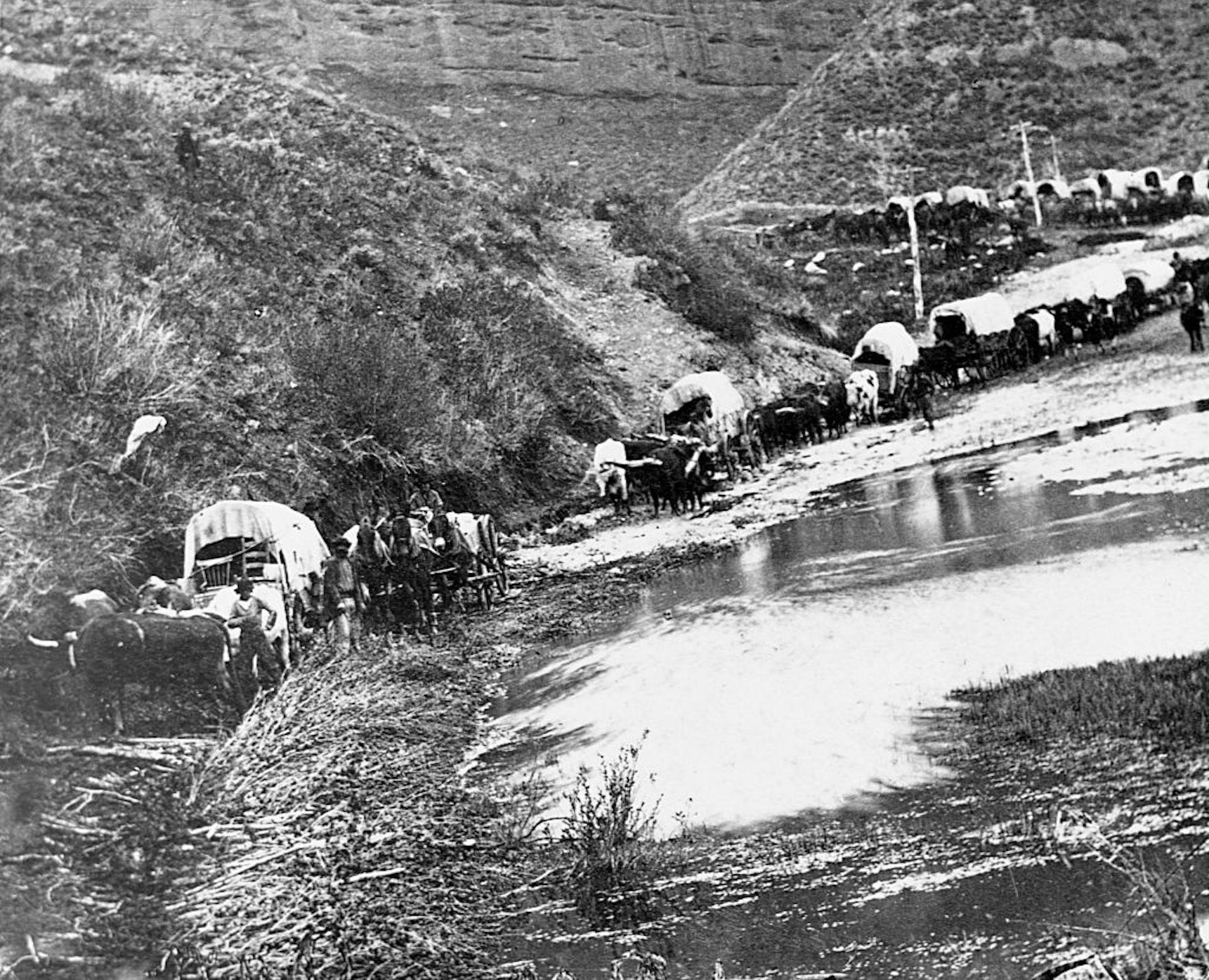

Historic 1879 image of Mormon pioneers traversing a river in covered wagons during their arduous journey west, commemorating Mormon Pioneer Day

Historic 1879 image of Mormon pioneers traversing a river in covered wagons during their arduous journey west, commemorating Mormon Pioneer Day

A covered wagon caravan of Mormon emigrants attempting a river crossing in 1879.

However, for some, Pioneer Day evokes feelings of exclusion and historical amnesia, particularly concerning the church’s impact on Native American populations. In a 2019 op-ed, Angelo Baca, a documentary filmmaker, and Erika Bsumek, a historian, highlighted that Pioneer Day represents “a key moment in the history of the colonization of the American West.” They argued it marked the beginning of a period where Ute, Paiute, Shoshone, Goshute, and Navajo peoples were dispossessed of “their homes, lands, and even, in some cases, their families.”

Pioneer Day also coincides with the anniversary of the arrival of Black individuals, both enslaved and free, whose experiences are often marginalized in traditional Utah narratives. Efforts to rectify this historical oversight include monuments and documented records that are prompting discussions about acknowledging and honoring their legacy during Pioneer Day.

As the membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints becomes increasingly globally diverse, Pioneer Day celebrations are beginning to incorporate a broader spectrum of “pioneer” narratives from the church’s global history. Recent church initiatives emphasize stories of contemporary pioneers who are actively building the faith worldwide, extending the pioneer narrative beyond its Utah-centric origins.

In conclusion, as Utah and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints continue to diversify, Pioneer Day celebrations are evolving to encompass a wider range of migration histories, experiences of displacement, and stories of courage. Through these evolving commemorations, participants continue to shape their present identity by re-examining and remembering the multifaceted narratives of their past.