The history of cinema is often attributed to names like the Lumière brothers and Thomas Edison, but what if the widely accepted narrative is incomplete? David Nicholas Wilkinson’s documentary, The First Film, throws a compelling spotlight on Louis Le Prince, arguing passionately for his recognition as the original pioneer of moving pictures. This film isn’t just a historical account; it’s a Yorkshireman’s determined quest to place Leeds, England, firmly at the heart of early cinema history by championing the Frenchman who may have beaten everyone to the cinematic punch.

Wilkinson’s documentary is more than a simple exploration of cinema’s origins. It’s a journey into the intertwined obsessions of two men: Le Prince, consumed by capturing motion, and Wilkinson, driven to elevate Le Prince’s legacy. This tribute, while occasionally meandering and lengthy, presents a fascinating, if somewhat eccentric, case for reconsidering the established timeline of film history and acknowledging a potential Pioneer Film visionary previously relegated to the footnotes.

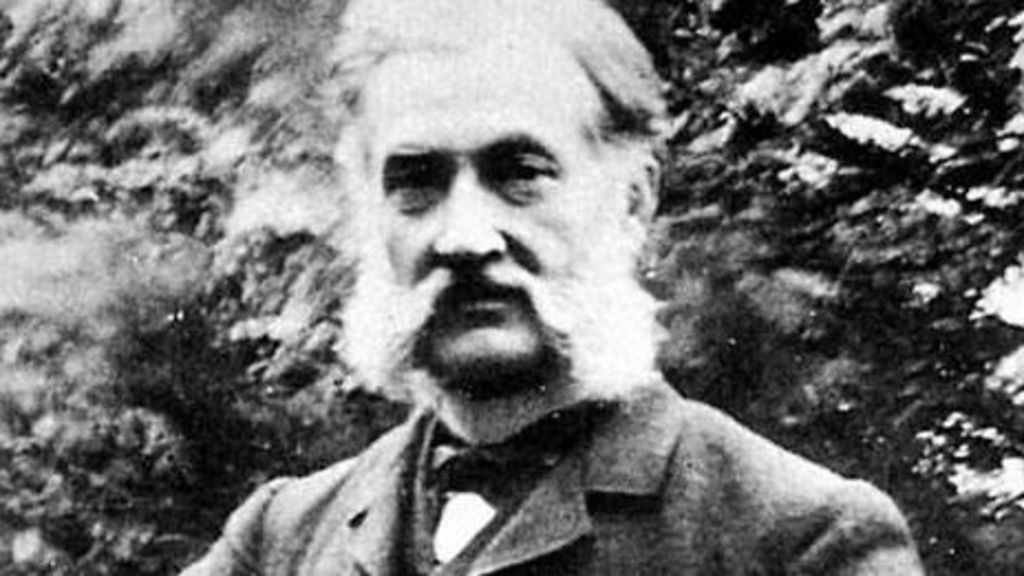

Inventor Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince, born in France in 1841, relocated to Leeds in 1869. After years of experimenting with various camera designs, including a multi-lens model, he achieved a breakthrough in 1888. Using a single-lens camera and paper film, he successfully recorded moving images. His surviving works include Roundhay Garden Scene, a charming glimpse of domestic life, and a film of Leeds Bridge. These short scenes arguably mark him as the first true movie-maker, the original “Father of Film,” predating his more famous contemporaries. This pivotal moment in pioneer film history occurred in the UK, a point of national pride and, according to Wilkinson, a source of overlooked credit.

Louis Le Prince

Louis Le Prince

Louis Le Prince, a French inventor who lived and worked in Leeds, is argued to be a true pioneer of film in the documentary “The First Film”.

So why isn’t Louis Le Prince a household name alongside other early film pioneers? Wilkinson suggests a combination of factors led to Le Prince’s obscurity. While Le Prince was innovating, figures like Edison, with his aggressive patent strategies, and the Lumière brothers, with their superior marketing, effectively overshadowed him. Wilkinson also points to a degree of British historical amnesia, citing The Magic Box, a biopic of William Friese-Greene, another British film pioneer, which notably omits Le Prince’s contributions. According to Wilkinson, a prevailing skepticism, particularly amongst “people in London,” further hindered the acceptance of Le Prince’s pioneering role in film.

A key technical detail often cited for downplaying Le Prince’s achievement is the fragility of his paper film, which prevented projection. Historically, projection was considered integral to the definition of moving pictures. Therefore, Le Prince’s groundbreaking work, while undeniably capturing motion, was sometimes deemed a near miss rather than the definitive birth of cinema. The advent of Eastman Kodak’s celluloid film in 1891, arriving after Le Prince’s disappearance, further solidified the narrative that bypassed his early innovations in pioneer film technology.

Adding another layer of intrigue to Le Prince’s story is his mysterious disappearance in 1890. While visiting family in France, he boarded a train from Dijon to Paris and vanished without a trace. This unexplained absence, occurring before the widespread recognition of the kinematograph, effectively removed him from the burgeoning history of cinema. The lack of a body and the absence of any definitive explanation for his disappearance only deepen the enigma surrounding this pioneer film figure, a point that Wilkinson explores extensively in his documentary. Wilkinson’s film becomes a dual investigation: a quest to solidify Le Prince’s place in film history and an attempt to unravel the mystery of his fate.

Undeterred in his mission to uncover “his” truth, Wilkinson’s documentary takes him from Leeds to Memphis, Metz, and Manhattan. He interviews a diverse range of individuals, from early cinema expert Stephen Herbert to screenwriter Joe Eszterhas, who offers a humorous critique of Edison. Perhaps the most compelling interview is with Louis Le Prince’s great-great-granddaughter, Laurie, who provides access to a treasure trove of her ancestor’s documents. Wilkinson’s dedication and the breadth of his research are commendable, reflecting his decades-long advocacy for Le Prince. However, the documentary’s focus on Yorkshire pride in claiming a Frenchman, who premiered his work in New York, as the first movie-maker, adds a somewhat quirky dimension to the narrative.

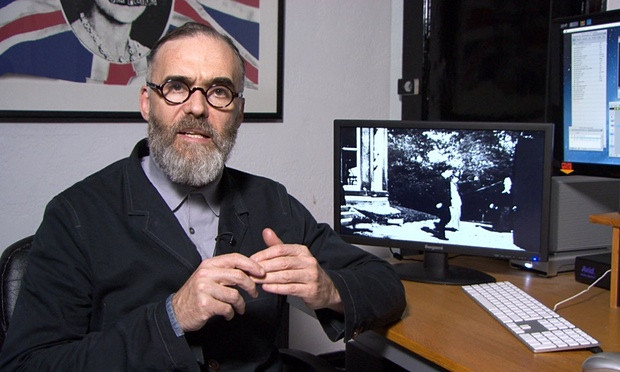

David Nicholas Wilkinson (and Roundhay Garden Scene)

David Nicholas Wilkinson (and Roundhay Garden Scene)

David Nicholas Wilkinson, director of “The First Film,” stands alongside an image from “Roundhay Garden Scene,” a key example of Louis Le Prince’s pioneer film work.

Despite its strengths in bringing Le Prince’s story to a wider audience, The First Film does have its shortcomings. While championing Le Prince is admirable, the documentary’s emphasis on being “first” risks overshadowing the broader, more nuanced story of the evolution of moving pictures. The film’s opening sequence, featuring industry figures and actor Tom Courtenay feigning ignorance of Le Prince, feels somewhat contrived. Similarly, the recurring segments where Wilkinson seeks validation from interviewees about his Le Prince theory come across as slightly self-indulgent. The documentary also suffers from pacing issues, feeling somewhat repetitive and overlong at times.

However, The First Film concludes on a high note with a charming re-enactment of Roundhay Garden Scene. Filmed on the original location with a replica of Le Prince’s camera, this scene, despite its slightly anachronistic suburban backdrop, is genuinely delightful. The infectious joy of the Le Prince enthusiasts operating the camera serves as a fitting tribute to his genius. Ultimately, the enduring value of The First Film lies in its passionate celebration of Louis Le Prince, ensuring that this overlooked pioneer film innovator receives the recognition he arguably deserves. The documentary prompts a valuable reconsideration of cinema’s origins and encourages a deeper appreciation for the contributions of figures who, like Louis Le Prince, may have been unjustly sidelined in history.